By Efraín Rincón and Maria Camila Agudelo

Before the dike bursts

The riot police surround a two-storey house constructed of salvaged wood. The owner, 35-year-old Yolanda Osorio, retrieves her family’s belongings just before the bulldozer razes her home of 20 years. She watches along with her 5- and 8-year-old daughters as the structure’s corrugated metal roof falls and the wooden walls lift a cloud of dust as they hit the ground.

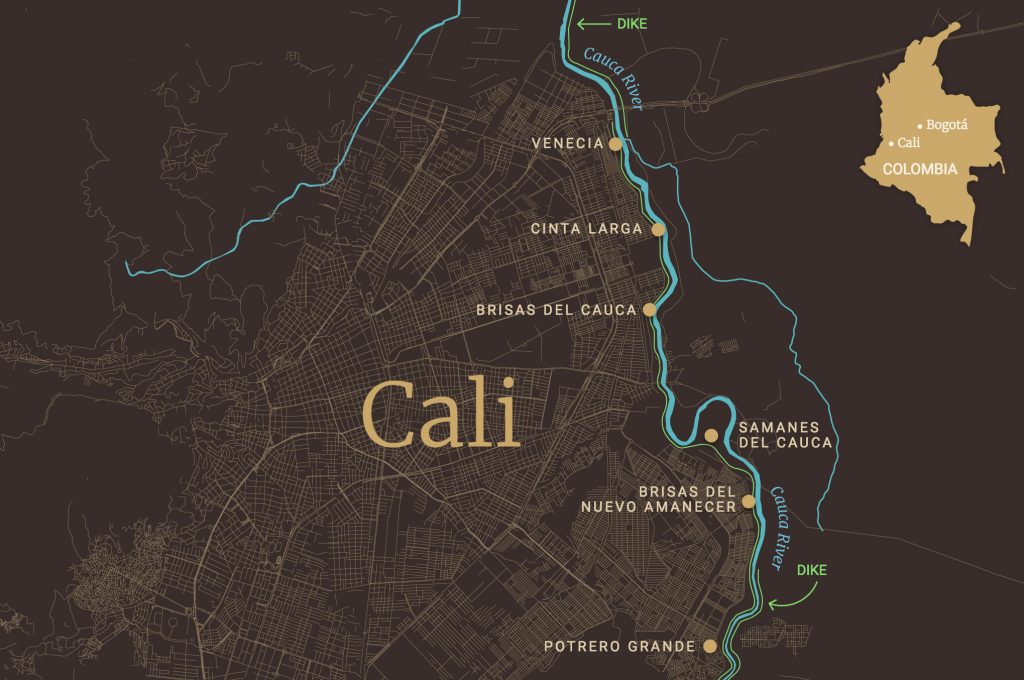

The cause of their eviction is the Cauca River that winds the eastern edge of Colombia’s southwestern city of Cali.

Climate change, the threat of extreme rainfall and the lack of city planning mean the city government needs to relocate more than 30,000 people living on the top of the Jarillon, a 23-kilometre dike that protects Cali from the river’s powerful waters. Decades of people living atop the structure have weakened it to the point that officials worry intense rains could cause the dike to break. Cali is just a few metres above the river level. If the dike fails one million people would be affected, homes and roads in eastern Cali would be flooded and 80 per cent of the city would be left without potable water.

Authorities estimate such a flood would cost more than $2 billion (U.S.) and the city would take more than 20 years to recover.

Cali Mayor Maurice Armitage says the evictions are crucial in order to protect residents from the river. (Alejandro Gomez)

“If the Jarillon of the Cauca River breaks today, I have no idea what will happen,” says Maurice Armitage, Cali’s mayor. “It would be a catastrophe of such magnitude that Cali surely isn’t ready for. It would be worse than (hurricane) Katrina in the United States.”

In 2011, Colombia suffered the worst rainy season in its history, affecting three million Colombians, uprooting thousands from their homes and destroying 3.5 million hectares of farmland. Cali was one of the worst hit regions. According to a United Nations report, climate change is making this kind of extreme rainfall more frequent, raising the risk of prolonged inundation in regions of the country that would not normally flood.

Cali has not yet seen another rainy season as intense as six years ago, but the threat has authorities concerned. This March, a landslide caused by rainfall killed 300 and destroyed dozens of neighbourhoods in the city of Mocoa, about 400 kilometres south of Cali.

These changes show how vulnerable Colombian cities are to climate change, which has caused temperatures to rise at a rate of around 0.1C per year since 1951, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “When temperature changes, air currents change, and if air currents change, the whole rainfall regime changes,” says Ricardo Lozano, the director of IDEAM, Colombia’s leading environmental investigation institute. As climate change has intensified Colombia’s rain patterns, the effects of El Nino and La Nina, Pacific Ocean climate cycles that alter global weather, have worsened.

Former IDEAM director Ricardo Lozano says the plan to reinforce of the dike does not take into account the Cauca River’s ecological structure.

Last year, Colombia endured heavy droughts caused by the second strongest El Nino in 50 years. The fear now is whether the next La Nina will cause an intense rainy season, similar to 2011.

That year, the Colombian government created a fund for large-scale projects to protect several parts of the country against climate change-associated floods and landslides. The plan to fix the Jarillon is one these projects.

The city of Cali has offered compensation to any evacuee of the Jarillon who was counted in the last census. But the community is not satisfied with the offer.

Not everyone in a house gets compensated — just the “owner.” That means only a few are likely to benefit in homes where six to eight people might live.

That is not enough for many families. Some former inhabitants have been forced to move in with neighbours, keeping their belongings in rented places while they wait for a new home.

What is more upsetting is how the government is using riot police to enforce the evictions. “Last Friday, they tore down the house of a lady who didn’t want to leave. She had small children,” Osorio says. “The bulldozer went behind the house and began to demolish it. The kids were inside with their belongings and animals. They don’t care about anything.”

Mayor Armitage says the evictions are crucial to defend Cali’s residents from the river. “Should I protect 8,000 families, or put in danger one million inhabitants in the city?” he asks.

The only major Colombian city with commercial access to the Pacific coast, Cali is the main urban centre in southwestern Colombia. The city has undergone rapid and disorganized population growth in the last 40 years, spurred on by a massive influx of displaced people. A series of natural disasters as well as decades of armed conflict with guerrilla groups like FARC and ELN have pushed huge numbers Colombians to migrate from the countryside to the major cities, putting enormous pressure on places like Cali. The government and FARC signed a peace accord last year, but Colombia still has the world’s largest population of internally displaced people — 7.4 million, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

In the 1970s, Cali’s metropolitan area could not meet its growing population’s demand for space. The lack of land forced newcomers to settle, often illegally, in the Cauca River’s floodplain on the then-rural east side. By the 1990s, around 700,000 displaced people were living in the new district of Aguablanca.

Cali is one of the 10 most dangerous cities in the world, according to the Citizens’ Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice. Last year, the murder rate in Colombia was 25 per 100,000 inhabitants. It was 54 per 100,000 in Cali, with almost half of those murders happening in Aguablanca — where the government is moving thousands of families evicted from the Jarillon.

Armitage says the families are squatters because the land on top of the dike is property of the state. “It is an attitude of illegal life. They are in a place that is not their own, it belongs to the community, they are not paying for public services,” he says.

The dike meanders along the Cauca River, marking Aguablanca’s eastern boundary. Almost 20 per cent of the population of Cali lives on the floodplain and about 15,000 people reside directly on top of the dike.

Juan Diego Saa is in charge of ‘Plan Jarillon,’ which Saa describes as the largest resettlement project in Latin America. (Alejandro Gomez)

“The first one who arrived here was my brother. He was one of the founders of Las Vegas neighbourhood,” Osorio says, referring to the 750 families whose houses were recently destroyed by the bulldozers. “He then brought my mom, my dad and his brothers to live here. My daughters were born here, too.”

According to “Plan Jarillon,” the government intends to resettle all 8,777 families who live along the dike, and then strengthen it.

“This is the largest resettlement project in Latin America. We are talking about almost 40,000 people who must be resettled,” says Juan Diego Saa, who Armitage has put in charge of the plan.

Cristina Paz, 75, lives on the Jarillon with her husband in a big house surrounded by animals and plants. “I feel like I’m in paradise here. I wake up at eight. Then, I feed the hens, birds, cats and dogs. At nine, I check my plants,” she says.

Paz’s livelihood is based on activities such as pig breeding, poultry, fish farming and cattle raising. Some of her neighbours have small recycling companies. Most of the houses nearby are made of salvaged wood, concrete and bahareque, a mix of cane and clay.

About 30 minutes by bus from Paz’s house, Blanca Medina and her two sons live amongst 1,749 families the government has already relocated to the Aguablanca’s Potrero Grande neighbourhood, which has the highest murder rate of any in the city.

Twenty years ago, Medina and her family built a large house right beside the dike. Like many of the residents, Medina and her family did not want to leave. “We knew it was a high-risk area, though it was very quiet and our life there was plentiful,” she says.

Now, she lives in a cramped brick house with a curtain separating the kitchen from the living room. “My mom had a shed of big chickens,” she says. “We had to leave our animals there. Here, there is no space to raise animals.”

Saa acknowledges the houses at Potrero Grande are significantly smaller, but he says the families will legally own their new homes.

Since there are not enough social housing projects in Cali to relocate people, the government negotiates compensation of between $70 and $80 per month for three months for each family, while the government finds a permanent solution.

Three months after she was evicted, Osorio has received just $210 in compensation. “We’re talking about some money to live for a few months, and what about later?” Osorio asks. She says unfairness in the compensations contributes to a climate of anger and despair.

So does the force with which some residents are being evicted. Osorio says every day riot police arrive with bulldozers, tear down one or two houses while the residents protest.

Saa insists the government is not using violence. “We are not using force during the evictions,” he says, adding that the project will inevitably have critics. “People don’t like change. In general, human beings would rather not to move.”

Once the evictions are complete, the government plans to reinforce of the dike by strengthening it with concrete and raising it 60 centimetres.

The changes could cause problems elsewhere, says Jorge Velez, a geographer at the Universidad del Valle in Cali. “We are concerned about what will happen to the communities that live at the other side of the Cauca River, where there is not a dike constructed.”

Plan Jarillon protects Aguablanca, but increases the risk to the rural communities that live across the river, Velez says. “I build a dike on one side to protect a population, but what I’m doing is moving the risk downstream, or in front of it.”

Other experts like former IDEAM director Ricardo Lozano question the plan’s effectiveness. “How are we adapting the Plan Jarillon to the current situation, where the ecosystem is altered and the river is full of sediments?” he asks.

Lozano says he believes that adapting a city to climate change should not interfere with the dynamics of the ecosystem, but that the plan to reinforce of the dike does not consider the Cauca River’s ecological structure.

How to adapt to climate change is not Yolanda Osorio’s main concern. After her house was torn down, she moved to a neighbour’s house, only to be evicted from there 20 days later, when it was also bulldozed. She is trying to find a place to rent that she can afford with her small subsidy. In the meantime, a neighbour is letting them stay at his house. “I expect that the government will give me a house, but it seems that it won’t happen. There is no hope.”