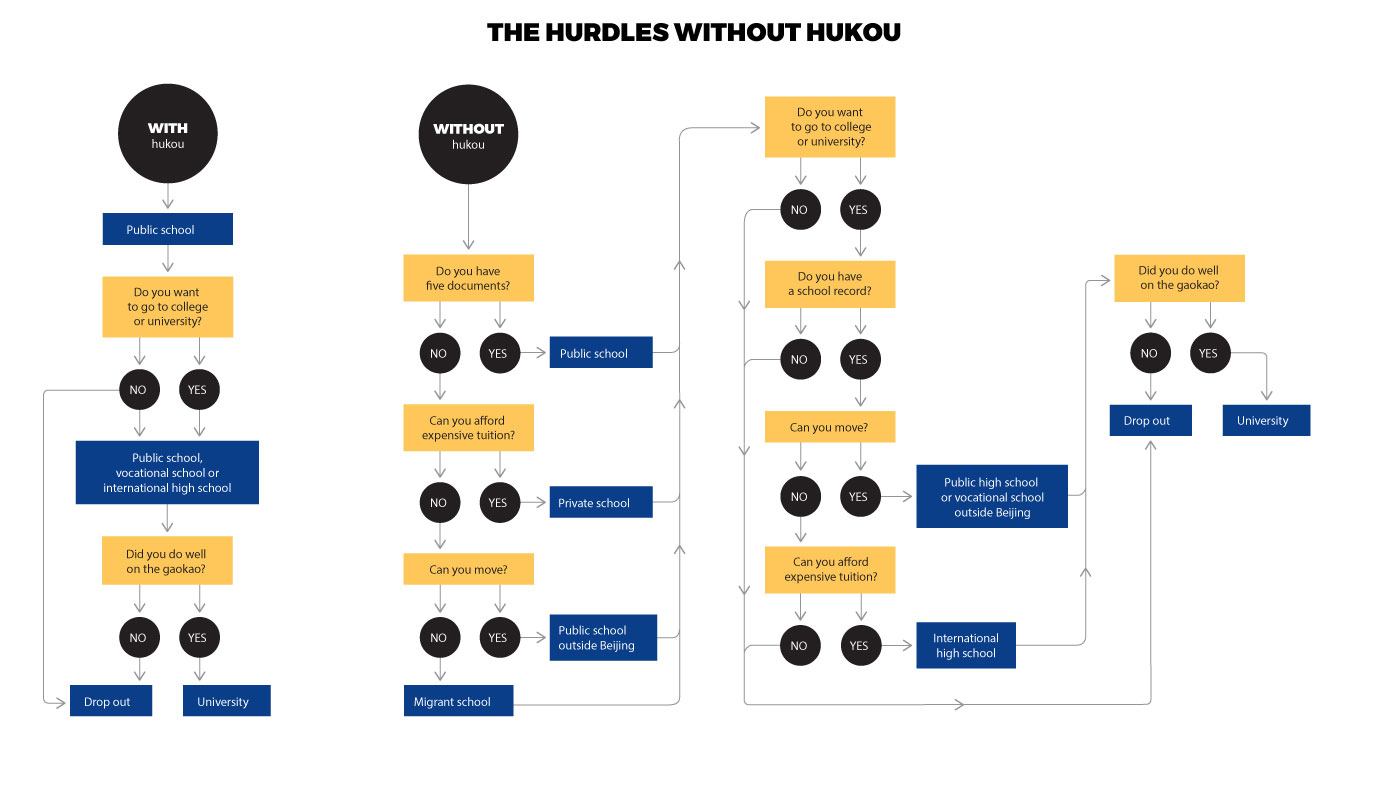

Chu Zhaohui, research fellow at the National Institute of Education Sciences, traces the current problem to 2014. That’s when Beijing launched the “Five Documents System,” which Chu says keeps 30 per cent of migrant students out of Beijing’s public schools. The system requires parents to submit at least five documents, such as proof of residence and employment. If they cannot meet the requirements, some parents send their children back to their home region, or send them to unlicensed migrant schools, which are effective dead ends.

In 2014, the city’s education commission took over student enrolment, and China’s central government implemented a national study permit system, which stores and maintains every student’s registration information. The system is intended to create efficiencies and remove barriers for children whose migrant parents often had to pay arbitrary “fees” to enrol their children in public schools, according to Chu.

But he says this hasn’t happened. “Since 2014, even if there are vacancies in the schools, it’s nevertheless impossible to persuade principals to admit students, because the schools no longer have the power to enrol students.”

Many migrant parents are unaware of the regulations, while others struggle to meet them. It can be especially hard for migrant workers to prove they’re employed. A 2009 survey found that less than half of migrant workers signed labour contracts.

Another blow followed — again in 2014 — when Beijing authorities implemented a policy excluding migrant kids from applying to Beijing universities. It meant a child of migrants born in Beijing has to leave the capital to pursue post-secondary education. This policy gave rise to the “migratory birds” phenomenon: children and teenagers of migrant parents flocking to the adjacent province of Hebei, where the rules are far more accepting of non-hukou holders.

In 2014, nine parents whose children were ineligible for Beijing’s college entrance exam took the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education to court, claiming the city’s education policy is unconstitutional for excluding migrant children from public education. They lost but continue to lobby the government, and they are not the only ones taking the extraordinary step of suing the city.

In October 2016, Huang Jiaming sued the same administrative body because his daughter was prevented from attending secondary vocational school. She had been rejected because Huang was unable to present the necessary five documents.

Huang Jiaming filed a lawsuit against the Beijing Education Commission in October 2016. He argued the city is violating the Chinese constitution

He argued that the requirement violates China’s constitution. “It didn’t take a lawyer to understand it’s against the law,” says Huang, who represented himself in court.

His daughter had obtained a study permit, allowing her to make it as far as middle school in Beijing. But Huang is unable to transfer her study permit to Henan so she is prevented from attending any public high school, putting her in a double bind. And because he doesn’t have social insurance, he can’t satisfy the requirements of the Five Documents System.

Chu Zhaohui says migrant students like Huang’s daughter often fall into a “grey area” and slip through the cracks. “Their hometown may keep their hukou but not their record of study, so when they go back home to study, they won’t have their study permit in their hometown as well. This is the problem that is happening,” says Chu.

In late December, Huang’s case was dismissed, but he has filed an appeal. “I didn’t put much hope in the [first trial]. The real hope I have is to take the case to the People’s Court.” This court is the equivalent of the Supreme Court of Canada, and could force Beijing to address the discrimination. “I would do anything for my kid, just to get her education, to demand the legal right for her,” says Huang.

Zhang Qianfan, professor of constitutional and administrative law at Peking University, agrees that the Beijing government is violating the law, which mandates that every child is entitled to public education. “Their parents pay taxes, (migrant children) study together, a lot of the time their grades are better than Beijing classmates . . . In every aspect they are the same except this seemingly irrelevant” hukou.

Much of the issue comes down to China’s challenge with migrants — the government needs cheap labour to fuel its heavily industrialized economy, but until very recently, the number of migrants has put an unsustainable strain on the capital.

“They make contributions to the city, therefore they think their kids have the right to enrol in a Beijing public school. But for the Beijing government, the first problem is overpopulation,” says Chu Zhaohui.

Since the early 1980s, China has opened up its markets and expanded its private sector economy, creating jobs for peasant workers in megacities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Migrants began to fill menial positions that local residents avoided even when unemployed. Between 1960 and 1970, the capital’s temporary population never exceeded 130,000. The eight million rural migrant workers in Beijing today make up roughly 40 per cent of the city’s population.

On March 17, 2016, the central government issued the latest Five Year Plan, intended to expand the country’s urban footprint by encouraging people to move to urban centres. But as China pushes for urbanization, the government is fighting to curb the population of its megacities.