The Game

Navid* was frantically pumping up an inflatable raft. Soon, it would carry him across the Maritsa River separating Turkey and Greece. He is one of roughly 70 migrants who had gathered on the riverbank, hoping to cross into Europe. The boats were almost inflated, when the men heard shouting in Turkish descending toward them. That could only mean one thing: police.

Navid shot a quick glance at his friends, Fathollah and Mohammed. Without a word they dropped everything, turned and darted off into the darkness.

The three men are Afghan migrants who entered Turkey illegally through Iran. They met each other in a safehouse after paying the same smuggler to take them to Europe. Fathollah is a teenager who dreams of being a boxer; Navid, 23, aspires to go to university; and Mohammed, 38, wants to reunite with his wife and three kids in Germany. In another life they might never be friends, but in this one they are united by the common goal of a new life in Europe.

Nestled between Asia, Europe and Africa, migrants have long used Turkey as a launchpad to a life in the West. The relatively lax migration regime, difficulty in patrolling long, rugged land borders with Iran, Syria and Iraq, and the short distance from its west coast to the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, all make Turkey an ideal location for transit en route to Europe.

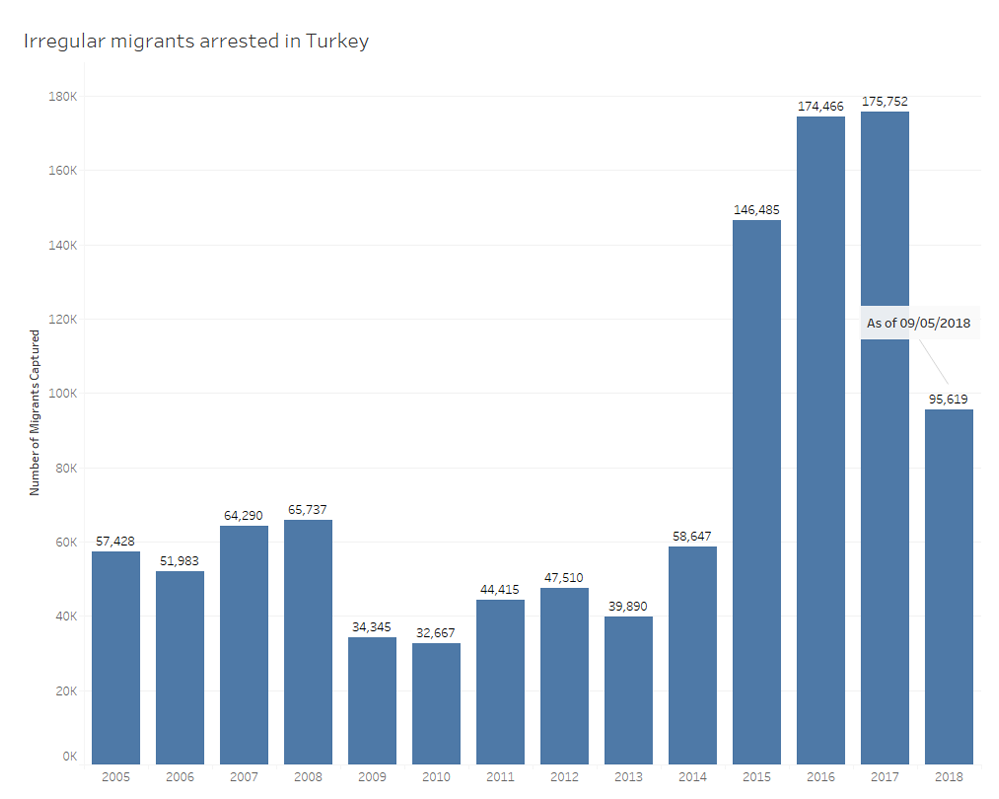

But in the wake of the Syrian crisis, the number of asylum seekers arriving in the European Union has skyrocketed, with 885,000 people coming through Turkey in 2015 — a 17-fold increase from the year before.

To stem the flow of migrants, the EU and Turkey signed a deal in 2016. In exchange for the equivalent of about C$8.6 billion in aid, Turkey agreed to prevent irregular migrants (those who don’t have authorization to work) from leaving its territory and to re-admit anyone who arrived illegally in Greece.

Chart and screenshot created with TableauView Interactive Version

Chart and screenshot created with TableauView Interactive Version

These are just numbers to Fathollah, Mohammed and Navid — a probability in the gamble they take every time they head out to the border. This time, they caught a break, finding a tiny shed near the river, where they hid from the police. But as soon as they made it back to Istanbul and through the blue, rusty door of the safehouse, they started talking about their next attempt.

“When you are hunting, you have your bow and your arrow and you pull the string but realize you held on to the arrow. You didn’t hit the target, but on the other hand, you’re happy that the target is still there. You can try again,” says Navid, who is on his fifth attempt in two months. He and the others have all been to Greece before, but each time they’ve been arrested and pushed back to Turkey.

“If we get arrested by the Greek police, we’re lucky if they push us back the same night,” says Fathollah. He’s young but frown lines already crease his face. The pushbacks are illegal under international law, which requires people fleeing into a country to be given a chance to apply for asylum. But Turkish authorities have accused Greek police of increasing illegal pushbacks. It’s easier for Greece to give migrants a ride back across the river than add another asylum request to their already overwhelmed system.

Each time the men fail, they return to the safehouse in Zeytinburnu, a migrant hub in Istanbul, where the smugglers will house and feed them until they can try again. They call these attempted rivers crossings the “game.”

Navid and Fathollah’s smuggler, who asked to be identified only as Feroz, says the game is becoming increasingly difficult.

“Nowadays, when people are calling me from Afghanistan and telling me that they want to go to Europe, I’m convincing them not to come,” says Feroz. But when he tells people that the way is blocked, that they could die in the process, it makes no difference.

“They are telling me that there is no hope for them [in Afghanistan]. They have nothing. So, I tell them, ‘Come if you want,’” he says.

At any given time, more than a dozen Afghan refugees stay in his 700 sq.-ft. safehouse with two bedrooms, one bathroom, a kitchen and a back door, to be used only in case of a raid. Dressed in camouflage pants and a black leather jacket, Feroz’s face is rugged, hardened over time, with a strong jawline and dark eyes that give nothing away.

“If I get arrested, it’s one to five years in prison,” he says.

His customers are rarely allowed to leave the house. When they do, they go alone or in pairs, mostly for groceries or cellphone repairs and only at night. Their phones and each other are the only entertainment they have. Navid is the life of the house, singing songs while cooking, cracking a constant stream of jokes and brandishing magic tricks with cards.

Fathollah is quieter, with a worried expression that rarely leaves his face. He says he got separated from his family when they were trying to cross the border from Iran and hasn’t been able to contact them since. He spent most of his life in Tehran, where he was an aspiring boxer. Though he hasn’t trained in months, he’s always dressed in a red tracksuit and keeps a small boxing glove keychain in his pocket.

In theory, all refugees in Turkey who want to reach Europe should register with UNHCR and apply for resettlement. But due to a backlog and 3.7 million Syrians overwhelming the system, Afghans have almost no chance of actually being resettled. Instead, they face an indefinite wait in Turkey, where they will be sent to a satellite city, one of 62 smaller municipalities away from the country’s borders and metropolitan cities.

“The resettlement system doesn’t work for Afghans, because no one would like to resettle any [of them],” says Abdullah Ayaz, acting director general for Directorate General for Migration Management, the Turkish civilian agency in charge of migration.

“If we prevent the irregular crossing to the EU side, we have to open a legal pathway for these individuals.” But he offered no explanation on what this pathway might be.

Navid tried the legal route to Europe, registering with UNHCR and entering the satellite city system. He was assigned to live in the coastal city of Zonguldak. It’s a beautiful city, he says, but being beautiful isn’t enough.

“I tried hard to find a job but I couldn’t,” he says. Unable to sustain himself in the city, Navid left Zonguldak, abandoning his legal status in Turkey and claim to asylum.

Fathollah, on the other hand, decided not to register at all, choosing to live as an undocumented illegal migrant. “It’s not worth it, because you don’t speak the language, you cannot find a job and you have to stay in that city,” he says, referring to how refugees are require permission from local authorities to leave their satellite city.

Fathollah came straight to Istanbul after crossing illegally from Iran. Mohammed, his uncle, was already in the safehouse. Word of mouth is normally how Feroz connects with his customers; his previous successes serve as a reference.

“My phone is my network,” says Feroz. By his own count, Feroz has helped 400-500 people cross the border. But he wasn’t always planning to be a smuggler.

He left Afghanistan about nine years ago with his sights set on England or Canada. When he made it to Istanbul, he started working in the informal economy, sending money back to his family and saving for the rest of the journey.

“After two years I decided to be a smuggler, because I could see that a lot of smugglers were harming Afghan migrants, not giving them food, not bringing them in the proper ways,” says Feroz. He had to change his tactics after patrols in the Mediterranean were increased following the EU-Turkey deal.

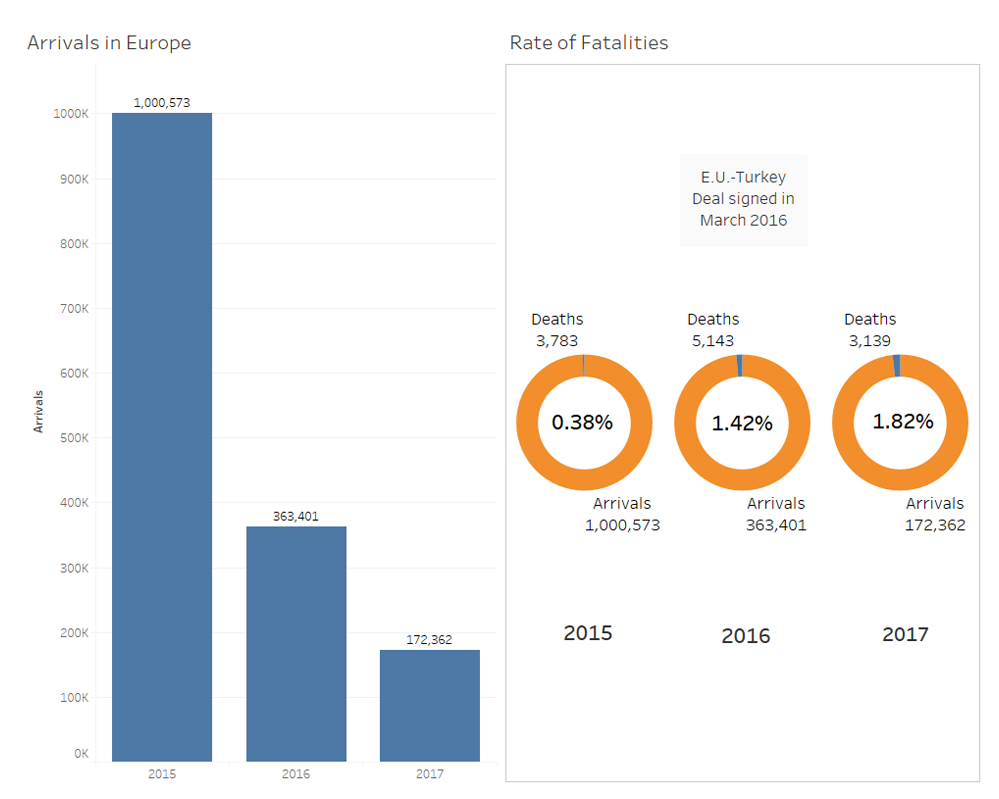

While the deal succeeded in reducing the number of migrants reaching Europe, deaths are proportionally on the rise as smugglers opt for more dangerous, less patrolled routes. Feroz says he hasn’t lost a single customer, yet.

Chart and screenshot created with TableauView Interactive Version

Chart and screenshot created with TableauView Interactive Version

“Every day when I wake up, I’m thinking about how to send people, how to find a way across the border,” says Feroz. These days, he directs people across the Turkey-Greece land border, most of which runs down the middle of the Maritsa River.

Normally, Feroz explains, the men are taken in a minibus toward the border. After they get dropped off, they join other groups of migrants, customers of different smugglers, and walk two hours through the forest. Relying on small flashlights and moonlight, they carry the inflatable rafts they need to cross the Maritsa river. If they make it to the Greek side, they’ll walk another two or three hours to the bus station where Feroz’s contact will hand them a bus ticket to Athens. If they make it that far, they’re on their own.

Navid, Fathollah and Mohammed are packing once again. There’s another game tonight. Navid is nervous, but he knows the drill. This will be his sixth attempt.

“Last time I tried [to cross the border] this way, I said it would be the last time. If I couldn’t pass, then I wouldn’t go again,” says Navid. “Then Feroz convinced me to try this route one last time and, if it doesn’t work, we will try another way.”

Navid’s wager paid off. He was separated from Fathollah and Mohammed, but they all boarded Greek buses. Navid’s bus made it to Athens, but his two friends hit a check stop. Fathollah and Mohammed were both arrested, taken back to the river and put in a boat back to the Turkish side.

Wet, cold and dirty, Fathollah and his uncle, Mohammed, returned to Istanbul but were caught by the police before they could reach Feroz’s safehouse.

“I was crying, telling them, ‘Please, leave me. I’m sick. I need to go to the doctor,’” says Fathollah, who was subsequently freed. He started pleading for Mohammed’s release as well. “They didn’t listen to me and told me that he will be deported.”

Fathollah hasn’t heard from Mohammed since. His only remaining family is gone.

“I’m feeling alone and lonely now,” he says. “I cannot sleep.”

* Some people featured in this story requested that their full names not be published as they fear deportation or detainment by authorities.