The Revolving Door

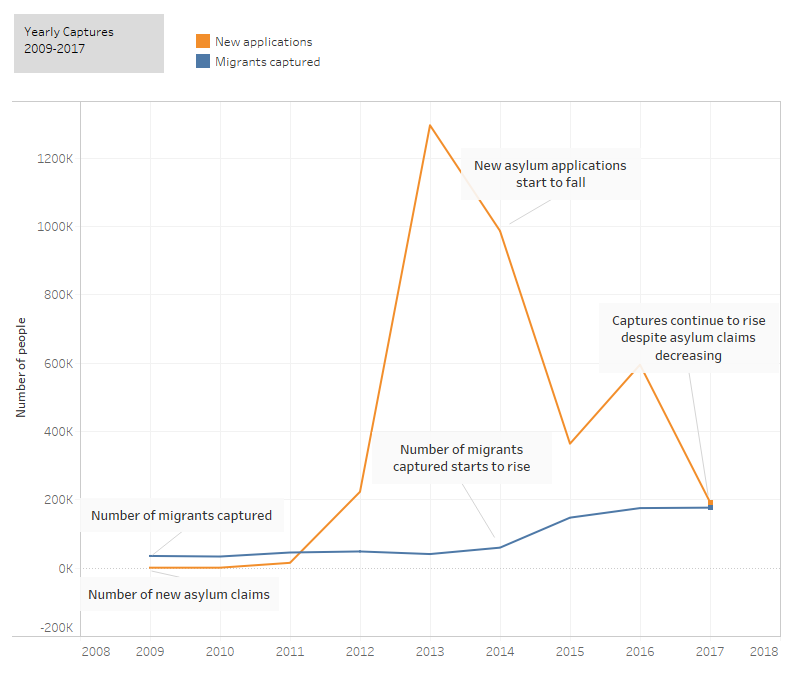

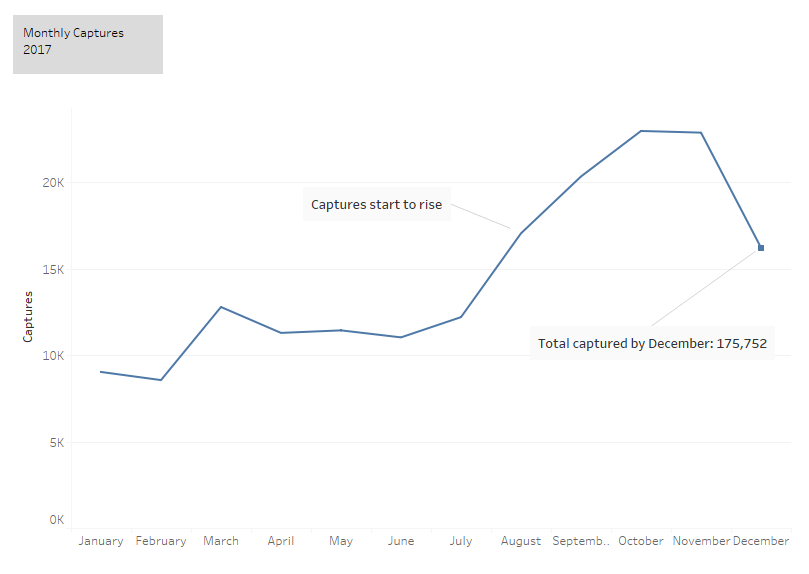

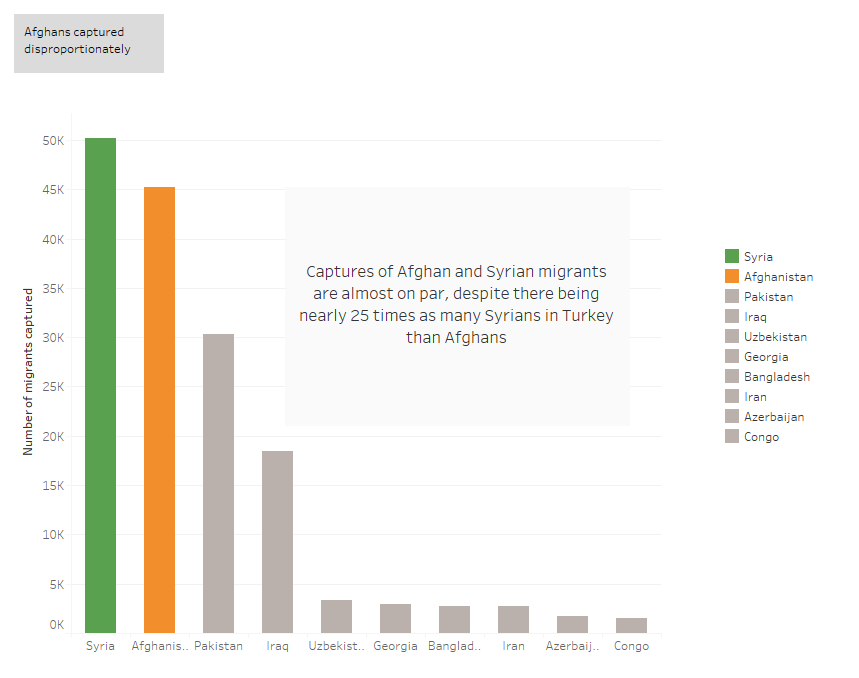

In the last three years, the number of illegal foreigners rounded up in Turkey has more than tripled compared to previous years — despite the falling number of asylum seekers entering Turkey. A data analysis of those statistics shows that a disproportionate number of these detainees are Afghans fleeing hardship and conflict in their country about 3,000 kilometres away.

“We provide shelter and protection to individuals who deserve international protection,” says Abdullah Ayaz, acting director of Turkey’s Directorate General of Migration Management. “The rest, we return to their country of origin.”

Turkey, like most countries, deports illegal foreigners, also known as “irregular migrants.” However, the line between illegal foreigner and asylum seeker is blurry, given that millions of asylum seekers use Turkey as a stepping stone to Europe. By cracking down on irregular migration, Turkey is also inadvertently detaining and deporting genuine asylum seekers rather than ensuring their protection.

Charts and screenshots created with TableauView Interactive Versions

Charts and screenshots created with TableauView Interactive Versions

Jaber Jafer is one of these people. He fled Afghanistan after the Taliban attacked the military station where he worked. He had hoped to apply for asylum in Europe, but ran out of money on the way. Jafer has been living and working illegally in Turkey for three years, trying to save enough to complete the journey. At least that was the plan until he got caught.

Late one night, a police truck pulled up outside the crumbling house in Istanbul where Jafer and a dozen other undocumented Afghan men live. The police gathered everyone and handed out sandwiches. They told the men they would help by issuing them ID cards. Not knowing they were being tricked, the men co-operated as the police took names and personal details. They were then handcuffed and escorted into the back of a truck. Jafer’s nephews, Sultan and Rehmat, watched the whole thing unfold.

“The police had only enough handcuffs for 10 people. They told us to go away,” says Rehmat. “So we ran.”

Sultan and Rehmat say it wasn’t always like this. They used to feel safe walking through the streets of Istanbul, but now they’re afraid of being stopped by police.

“If you came to our place two or three months ago, there were 70 or 80 guys living here. Some of them are stuck in prison now, some of them were deported,” says Rehmat.

Data suggests that Afghans in particular seem to be targeted. Undocumented Afghans accounted for 10,000 of 28,000 total deportees from Turkey last year. Early this year, a surge in arrivals from Afghanistan triggered mass deportations, with 7,000 Afghans sent home between January and April. Turkish officials plan to remove thousands more by the end of this year.

“All countries are quite reluctant to take migrants, especially Afghans,” says Ayaz. “So most of them apply to stay in Turkey, which is of course not the solution.”

Even though Ayaz acknowledges the situation in Afghanistan is deteriorating and driving people to leave, he believes Turkey must respond by increasing the capacity of detention centres and continuing with deportations.

According to Amnesty International, sending undocumented Afghans home is a violation of international law, which prevents the return of asylum seekers to unsafe countries. But Turkey considers Afghanistan “safe,” despite the fact more than 10,000 civilians were killed or injured in conflict last year, and 1.2 million Afghans are currently internally displaced.

“No part of the country is safe,” says Anna Shea of Amnesty International. “There is no doubt that Turkey is under pressure — it has accepted huge numbers of refugees, mostly financed from its own budget — but these deportations will put lives at risk.”

The recent roundups and deportations have generated a climate of fear among Afghan asylum seekers.

“Today I went to the consulate, so I put on these nice clothes,” says Rehmat, tugging on his moss-coloured, traditional Afghan garments. He was at the consulate trying to help his uncle. “If they deport me today, at least I’ll go home in some nice clothes.”

Although safeguards are written into Turkish law to ensure detained foreigners have the opportunity to apply for asylum, detainees either don’t know they can make a claim, or run into barriers trying.

Researcher Maybritt Jill Alpes tracked 1,144 non-Syrians sent back to Turkey from Greece. Only five per cent successfully filed an asylum claim from within detention centres, and only two were eventually granted refugee status.

Tomáš Boček, a special representative for the Council of Europe, visited four detention centres in 2016. Although authorities assured him that detainees are given pamphlets outlining their right to apply for asylum, he was unable to find these documents in the centres he visited. The detainees Boček interviewed said they had not received any information on their rights and several of their requests for asylum were ignored. He also met non-Syrian detainees, who said they were under pressure to sign voluntary return agreements.

It’s also harder for lawyers to help detained asylum seekers with their claims. They used to be able to visit centres to source clients, but are now denied entry unless they already have power of attorney over a case, which is nearly impossible when detainees have little contact with the outside world.

The centres are generally kept out of sight and few people are granted access to visit. There is no central database of the locations of these so-called “removal centres,” but we created a map of those we believe to exist throughout the country, along with their capacities.

Completed Removal Centers

Under Construction (as of June 2018)

Ten years ago, Turkey’s removal centres could house fewer than 1,000 people. Today, they can hold more than 8,000. Capacity is set to reach 15,500 in the next year with funding from the EU to build new facilities, which is indicative of Turkey’s long-term plan to control migration and Europe’s vested interest in doing so.

Jafer was taken to a removal centre in Silivri, about an hour’s drive from Istanbul. He calls Sultan and Rehmat from a payphone inside the centre and only has five minutes to talk — his cellphone was taken away. Jafer says the cells are cramped and he isn’t receiving enough food, even when he bribes the guards with money. Nobody told him why he was detained or if he’ll be released.

Sultan and Rehmat are worried about their uncle, Jafer. They’d prefer if he was deported back to Afghanistan, where he could turn around and leave again, as many returned Afghans do.

“If they don’t let him go in three days,” says Rehmat, “I’m going to go back to the consulate and tell them that they can’t keep this guy for a month and feed him half a loaf of bread and a tomato. He’s not going to end up being the same person he was when he went in.”

After almost a month in detention, Jafer is finally freed. The other men arrested on the night of the raid were all deported.

“The police came and asked us at one point, ‘Do any of you have problems if you go back home?’ and the other men didn’t say anything. They were deported,” says Jafer. “And when they asked me, I said, ‘Yes, I have these problems,’ and they let me stay here.”

Jafer was given a letter stating that a deportation decision still needs to be made. He must provide proof he was in the Afghan army and check in with authorities every 15 days until his documents arrive. After that, he can register for asylum, which brings about other challenges for non-Syrian refugees. He’ll be sent to a satellite city to live indefinitely with little hope of resettlement. If he’s ever caught leaving his assigned city without permission, he’ll be immediately deported and barred from applying for asylum in Turkey again.

Ayaz admits the system isn’t perfect, but he says it’s a success given the immense pressure on the country. Until there’s stability in Afghanistan and the region, he says, migrants will keep arriving, and Turkey will keep combating irregular migration.

“It’s not fair to criticize Turkey about the migration issue. Currently we are doing our best,” says Ayaz, who says the solution is for other countries to step up to help bear the burden. “This is not the crisis of Turkey, not the crisis of North America, of Greece, not the crisis of the EU. These are the crises of humanity.”